.svg)

Way back in 1977, Polar Electro unveiled the world’s first personal heart rate monitoring device. They used it as a training aid for the Finnish National Cross-Country Ski team and was a far cry from today’s slick iterations. Retail sales of wireless personal heart monitors started in 1983 and by the mid-80s “intensity training” had become a popular concept in athletic circles.

Here we are, 4 decades later, and this ancient device is still the only item of fitness tech you really need. Allow me to explain…

A heart rate monitor is a device that tells you how many times per minute your heart is beating. It does this through one of two methods: ECG (the measurement of electrical activity in your heart) or PPG (light sensors that measure the pulse caused by contraction of your heart).

Chest straps produced by companies like Polar, Garmin, Suunto, and Wahoo use ECG technology that is extremely accurate and reliable if worn correctly. Newer versions have in-built memory and can even measure more sophisticated data like heart rate variability (see our dedicated article). However, they aren’t practical, comfortable or fashionable enough to be suitable for all-day heart rate monitoring.

Modern smartwatches and fitness trackers (including the Apple Watch) make use of PPG technology to measure heart rate from the wrist. Although this technology has improved, it is still not as reliable or accurate as an old-school chest strap, especially in the cold or during vigorous exercise. You can trust the data from these devices during sleep and quiet time, but should take the data measured during exercise with a pinch of salt.

If accuracy is important to you (I believe it should be), stick with a chest strap to guide your exercise sessions.

One day, that heart of yours is going to stop beating. Assuming you’d prefer that day to be a long time from now, heart rate monitoring is the simplest way to keep track of your fitness and your heart health.

There are whole textbooks written on the intricacies and applications of heart rate monitoring, but for mere mortals, it is more than sufficient to understand 3 simple concepts.

1. Resting heart rate (RHR)

This is your heart rate when you are sitting calmly, feeling relaxed, and don’t have any stimulants (like caffeine) flowing through your veins. It is best measured in the morning, before the chaos of the day ensues.

A lower number is better and signifies a heart that is pumping efficiently and doesn’t need to work hard to meet the metabolic demands of your body. Trained athletes will often see numbers under 50 beats per minute, but look out if yours is up around 80 or 90 beats per minute as that can be a sign of heart or metabolic disease.

Here is a scary stat: for every 10-beats-a-minute increase in RHR, the risk of dying from any cause rises 9%, and the risk of dying from heart disease rises by 8%. The best way to get this number down? Regular cardiovascular exercise, of course.

2. Maximum heart rate (MHR)

This is your heart rate at its absolute limit. Athletes will know the feeling - lungs burning, muscles screaming, brain fading, and heart pounding. We can only hold this level of work for a very brief time, but knowing the number is useful for setting up heart rate training zones.

Our MHR declines steadily as we age and so the most common method for estimating MHR is the well-known formula HRM = 220 - (age in years). Using the formula, we can estimate that a 40-year-old person’s MHR is 180. Simple.

Except it isn’t.

While this formula (and other similar ones) can get you to a ball-park estimate of MHR every heart is different. For most people, the formula will be accurate enough to guide training, but some people might not even get close to their supposed MHR while still others shoot past it while taking a stroll on the beach.

The only way to get an accurate figure is to do some field testing. If you are an athlete who regularly pushes yourself to the max, have a look back at the data from past sessions and find the highest heart rate recorded. Otherwise, head to a track to do a maximum heart rate test to find your true number. Interestingly, you may find that your MHR is different during running than it is during cycling or other sports.

Important: performing a maximum heart rate test is not safe for everyone, so please run it past your doctor first.

3. Heart rate zones

Once you have your MHR (via the equation or the test), use it to figure out your heart rate training zones using this easy to remember 5 zone model:

Zone 1 | 50 - 60% of MHR

Zone 2 | 60 - 70% of MHR

Zone 3 | 70 - 80% of MHR

Zone 4 | 80 - 90% of MHR

Zone 5 | 90 - 100% of MHR

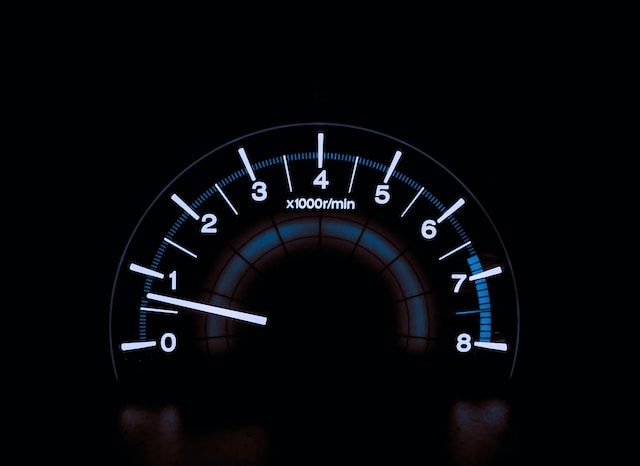

An easy way to think about heart rate data is to use a car analogy (apologies to the non-petrol heads in the crowd):

You are the car.

Your heart rate is the rev counter.

Your performance is the speedometer.

I.e. Heart rate is a measure of how hard your engine is working, not how fast you are going or how much power you are producing. Some cars are more efficient (fit) than others and can go really fast without revving too high, while more inefficient (unfit) cars need to rev their engines to 7000 RPM just to get off the start line. Fortunately, your car is amazingly adaptable, and it gets more efficient every time you take it for a drive or even rev the engine a bit.

We can therefore use our rev counter to measure and track our fitness. Look out for these signs of improving fitness:

A lower resting heart rate

Higher pace or power for the same exercise heart rate

Lower exercise heart rate for the same pace or power

Unfortunately, the opposite is also true. If your rev counter shoots up higher than before at an easy speed, it means your engine has become less efficient.

We can torture this analogy even further for the overachievers: your car is a hybrid. It has an efficient, clean-burning electric engine (fat) and a less efficient petrol engine (carbohydrate). At low revs, the electric engine does most of the work, but as the rev counter ticks up, the more powerful petrol engine has to contribute more and more and burns up fuel at an alarming rate.

That really depends on what your goals are. For most people who are looking to improve their fitness, lose some weight and enjoy the amazing health benefits of regular exercise, spending lots of time in zones 2 and 3 will be the best bet. Around 80 - 90% of training time, to be precise. Dedicate the leftover 10 - 20% of training time to higher intensity intervals where you crank up the effort to zones 4 and even 5 for short durations. We should separate these more intense sessions by easier days or rest-days, as they can be very fatiguing. Gradually increase your weekly exercise hours by only 10 - 15% to avoid injury and over-training.

And that is really as complicated as it needs to be. Keep it up for a month or two and you’ll soon see your pace quickening, your breathing calming, and your heart rate slowing - signs of an athlete in the making.

HRV monitors, continuous glucose monitors, muscle oxygen monitors, body temperature monitors, power meters, cadence meters, sleep sensors…

Despite being bombarded with new fitness tech almost daily, it is reassuring to know that you can be fit, fast and healthy using nothing more than the humble heart rate monitor.